We are re-posting this excellent, thought-provoking piece by Sayantani DasGupta, “Your Women Are Oppressed but Ours Are Awesome”: How Nicolas Kristoff and Half the Sky Use Women Against Each Other, originally from the blog Racialicious, as it lucidly articulates a number of themes that are key to the White Noise Collective’s analysis. While acknowledging the tremendous work that many people are engaged in (including Kristoff) to bring awareness to vast realities of gender-based violence, DasGupta critically draws out the recurring dynamic of the white savior industrial complex, the Global North feminist imperialist “gaze” on women of the Global South, the power dynamics of speaking for others, problematic representations, reinforcing notions of cultural superiority and paternalism while seeking to help.

“Postcultural critic Gayatri Chakrovorty Spivak, in fact, coined the term “white men saving brown women from brown men” to describe the imperialist use of women’s oppression as justification for political aggression.”

How has this dynamic been deployed in justifying US wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, with the added dimension to Spivak’s formulation of, “white women saving brown women from brown men”?

Solidarity and “sisterhood” across borders are undermined by these dynamics. Pointing them out is in the service of finding ways to challenge gendered oppression without reproducing “well-intentioned” racism, “othering”, and forms of dehumanization within the dynamic of aid/help/empowerment/saving, that have long histories and entrenched patterns. We need to see them with new eyes.

“Your Women Are Oppressed, But Ours Are Awesome”: How Nicholas Kristof And Half The Sky Use Women Against Each Other

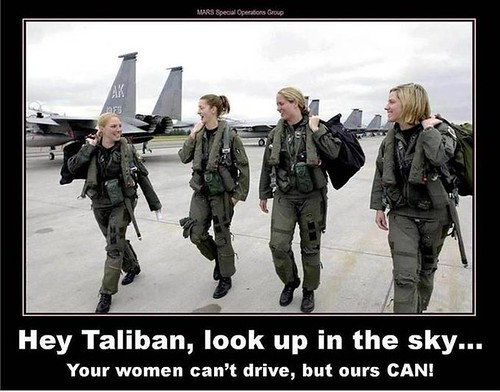

I just saw the most problematic image on Facebook. It was a photo of four blonde female pilots in combat gear with the caption, Hey Taliban, look up in the sky! Your women can’t drive, but ours CAN!

Despite the issues I have with militarism, or this country’s campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, I’m all for cheering for female pilots (yea, bada&& flying ladies!). What I can’t just can’t stand by and let slide is this “your women are oppressed, but ours are awesome” rhetoric, a rhetoric which only illuminates how–both actually and metaphorically–racism, xenophobia, and imperialism so often play out on women’s bodies around the world.

To me, this photo represents how blithely and blindly women from the Global North allow ourselves to be used as (actual and metaphorical) weapons of war against women from the Global South. In fact, that offensive caption isn’t significantly different from comments I’ve been hearing this week like, “These are countries where women have very little value.”

Sadly, the place where I’ve been hearing such phrases isn’t on some conservative TV program or website (where I think that all-woman pilot photo originated), but rather, on the PBS film Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women, a well-publicized neo-liberal “odyssey through Asia and Africa” hosted by everyone’s favorite white savior New York Times reporter, Nikolas Kristof.

New York Times reporter Nikolas Kristof in “Half The Sky.”

New York Times reporter Nikolas Kristof in “Half The Sky.”Inspired by a book co-written by Kristof and his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, and supported by talking head cameos from the likes of Hillary Clinton, Gloria Steinem, George Clooney, and officials from the United Nations, CARE, and other non profit and development organizations, the film, unfortunately, reeks of KONY 2012 style missteps. In fact, in ‘white man’s burden’ style, Kristof even says at one point, “When you have won the lottery of life that there is some obligation some responsibility we have to discharge.”

Perhaps reflecting this sense of noblesse oblige, the film is based on an amazingly problematic premise: the camera crew follows Kristof as he travels to various countries in the Global South to examine issues of violence against women–from rape in Sierra Leone, to sex trafficking in Cambodia, from maternal mortality and female genital cutting in Somaliland, to intergenerational prostitution in India. Because, hey, all the histories and cultures and situations of these countries are alike, right? (Um, no.) Oh, and he doesn’t go alone! Kristof travels with famous American actresses like Eva Mendez, Meg Ryan, Diane Lane, Gabrielle Union, and America Ferrera on this bizarre whirlwind global tour of gender violence.

There are plenty of critiques I could make of Kristof’s reporting (in this film and beyond, see this great round-up of critiques for more). Critiques about voyeurism and exotification: the way that global gender violence gets made pornographic, akin to what has been in other contexts called “poverty porn.”

For example, would Kristof, a middle-aged male reporter, so blithely ask a 14-year-old U.S. rape survivor to describe her experiences in front of cameras, her family, and other onlookers? Would he sit smilingly in a European woman’s house asking her to describe the state of her genitals to him? Yet, somehow, the fact that the rape survivor is from Sierra Leone and that the woman being asked about her genital cutting is from Somaliland, seems to make this behavior acceptable in Kristof’s book. And more importantly, the goal of such exhibition is unclear. What is the viewer supposed to receive–other than titillation and a sense of “oh, we’re so lucky, those women’s lives are so bad”?

In her book Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag suggested that images of distant, suffering bodies in fact inure the watcher, limiting as opposed to inspiring action:

Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers. The question of what to do with the feelings that have been aroused, the knowledge that has been communicated. If one feels that there is nothing ‘we’ can do — but who is that ‘we’? — and nothing ‘they’ can do either — and who are ‘they’ — then one starts to get bored, cynical, apathetic.

The issue of agency is also paramount. In the graduate seminar I teach on Narrative, Health, and Social Justice in the Master’s Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University, I often ask my students to evaluate a text’s ethical stance by asking themselves–“whose story is it?” For example, are people of color acting or being acted upon? Although the film does highlight fantastic on-the-ground activists such as maternal-health activist Edna Adan of Somaliland, the point of entry–the people with whom we, the (presumably) Western watchers, are supposed to identify–are Kristof and his actress sidekick-du-jour.

In fact, many have critiqued Kristof for his repeated focus on himself as “liberator” of oppressed women. As Laura Augustín points out in her essay “The Soft Side of Imperialism”:

Here he is beaming down at obedient-looking Cambodian girls, or smiling broadly beside a dour, unclothed black man with a spear, whilst there he is with Ashton and Demi, Brad and Angelina, George Clooney. He professes humility, but his approach to journalistic advocacy makes himself a celebrity. He is the news story: Kristof is visiting, Kristof is doing something.

Beyond his self-promotion, there remains the issue of whose story Kristof is telling. He has, in fact, answered critiques of his reporting style–which often focuses on white outsiders going to Asian or African countries–by saying that this choice is purposeful. When asked why he often portrays “black Africans as victims” and “white foreigners as their saviors,” he has answered, “One way to get people to read…is to have some sort of American they can identify with as a bridge character.” A presumption which assumes that all New York Times readers are white, of course, but I won’t get into that now.

Finally, and most problematically, Half the Sky replicates the same dynamic of that dreadful pilot photo by focusing solely on the oppressions of the Global South.

Although a few passing comments are made about rape, coerced sex work, and other gender-based violence existing everywhere in the world–including in the U.S., hello?!–the point that is consistently reiterated in the film is that gender oppression is “worse” in “these countries”–that it is a part of “their culture.” In fact, at one point, on the issue of female genital cutting, Kristof tells actress Diane Lane, “That may be [their] culture, but it’s also a pretty lousy aspect of culture.”

There’s nothing that smacks more of “us and them” talk than these sorts of statements about “their culture.” Postcultural critic Gayatri Chakrovorty Spivak, in fact, coined the term “white men saving brown women from brown men” to describe the imperialist use of women’s oppression as justification for political aggression.

Although Spivak was writing about British bans of widow burning and child marriage in India to make her point, we can see the reflections of this dynamic is the way that the US has justified wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as missions to “free Islamic women from the Veil.” (For a fantastic critique of this rationale, see Lila Abu-Lughod’s “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving?“) According to Spivak, this trope of “white men rescuing brown women from brown men” becomes used to justify the imperialist project of “white man” over “brown man.”

And this formulation is consistent, pretty much across the board, with the film. White/Western dwelling men and women highlight the suffering, as well as local activism, of brown and black women. Brown and black men are portrayed consistently as violent, incompetent, uncaring or, in fact, invisible. And it’s only a small leap to realize that such formulations–of countries incapable of or unwilling to care for “their” women–only reinforce rather than undermine global patriarchy, while justifying paternalization, intervention–and even invasion of these “lesser” places–by the countries of the Global North.

Actress America Ferrera in “Half The Sky.” Via Zap2it.com

Actress America Ferrera in “Half The Sky.” Via Zap2it.comI’m certainly not making the case that gender-based violence is a good thing. Of course, we should work against it in our own personal location; of course, we should focus (as part of the film does) on, support, and follow the lead set by those fantastic global activists already organizing around these issues in their particular locations. The problem becomes when the process of international support takes on more importance than it should–when the shocked look on Meg Ryan’s face or the tears on Diane Lane’s or the colorful-exotic shots of Western-attired Olivia Wilde dancing with traditionally dressed and bead-wearing Kenyan village women becomes the primary focus.

And these actresses are not there to share, say, their own stories of gender violence, or because they are already involved in anti-gender violence work in the U.S. or even work already going on in these countries. Rather, they are there as tourists of violence, often visiting those countries for the first time with Kristof. They are wealthy celebrities whose lives, as Meg Ryan tells one sex trafficked Cambodian teen, are “far from” the experience they were witnessing. As well-known, even aspirational, figures to most Western viewers, they not only mediate the viewer’s relationship to the local women but mandate the viewer’s visual and emotional allegiance. Their mere presence interferes with the viewer’s ability to feel any true sense of affiliation with those local African or Asian women. Instead, they unwittingly reinforce the “your women are oppressed, but ours are awesome” dynamic.

I don’t mean to say that these actresses–or Kristof and WuDunn, for that matter–don’t mean well. They clearly do. The problem is that sometimes good intentions can do bad work; supposed “solutions” can effectively reinscribe the same dynamics between Global North and South that created the global economic and political inequities that facilitate gender based violence in the first place.

As feminist philosopher Linda Martín Alcoff argues in her essay “The Problem Of Speaking For Others,” that part of the problem of speaking for others is that none of us can transcend our social and cultural location: “The practice of privileged persons speaking for or on behalf of less privileged persons has actually resulted (in many cases) in increasing or reinforcing the oppression of the group spoken for,” she writes.

To Kristof’s and WuDunn’s credit, Half the Sky is clearly trying to bring attention to issues of global gender violence, mobilizing the celebrity status of a group of actresses toward this goal. Also to his credit, Kristof highlights the work of a local, on-the-ground activist during each “celebration of oppression” segment, and there is somewhat of a focus on women’s empowerment, at least by the end of the film.

As we in gender activism and public health have known forever, the film is right: educating, empowering, and organizing women makes healthy families, strengthens communities, and supports national growth. Yet, ultimately, the very nature of the film itself undermines its stated goals of global female empowerment. By telling other peoples “their” women are oppressed, while “our” women are awesome, Half the Sky undermines global sisterhood rather than strengthening it.