The replacement of real indigenous stories with Christian-influenced, western moral tales is colonialism, no matter how you dress it up in feathers and moccasins. It silences the real voices of native peoples by presenting listeners and readers with something safe and familiar. And because of the wider access non-natives have to sources of media, these kinds of fake stories are literally drowning us out. – âpihtawikosisân

There is a story that we keep getting told. A lot. It is about two wolves. In different spaces- as a student I was recounted this by a teacher, now as a teacher, I have heard it several times from students. In yoga classes, in spiritual, psychological self-help and healing curricula, occasionally by a friend or acquaintance. Perhaps you have heard it too. It goes like this:

(big meaningful inhalation)

Once upon a time, there was a Cherokee grandfather (or Navajo grandfather), who told his grandson, “Grandson, there are two wolves inside of me. One wolf is white, good and altruistic, generous and kind, and the other wolf is black, mean and greedy, violent and angry. The two wolves are in a constant fight within me.” The grandson, with wide eyes, says, “But which one will win, grandpa?” And the grandfather says (there is usually a deliberate pause here for effect before delivering the spiritual punchline – wait for it), “The one which I feed.”

Every time I have heard this story told, there is a similar pause, and then a moment of suspension before the wisdom gem is transmitted and the coin drops. Sounds of understanding, nodding, smiles, “ahh, yes!” “oh i love that story!” usually follow. It then gets spread further. The person having told the story smiles and nods and takes in the shared insight, reveling in the experience of others’ illumination, as they were when they first heard it.

Recently at a yoga class in San Francisco, the mostly white students were told the story by a white teacher at the beginning, and at the end, we were instructed to “bow to the white wolf within”. Buddhist nun Pema Chodron has a whole two wolves curriculum, on how to feed the white wolf. In a Psychology Matters article “The story of the two wolves: managing your thoughts, feelings and actions”, the tagline reads: “Knowing which wolf you feed is the first step towards recognizing you have control over your own self.”

It has become a social media meme.

What is it about this story that makes it so enjoyable to hear and tell for non-Native folks? And for most of whom are white settler descendants?

Elements of story:

- It is authentic. How do we know? Because it is a Native American story. And it is “old”. Nothing more needs to be asked. With the genocidal distance of time and space, authenticity is not questioned or checked.

- It is easy to understand – we heart binaries, especially white and black, good vs. evil.

- It gives agency and control – we can feed what we wish to strengthen. This is very positive!

- It is very individualistic. i.e. people are shaped by their strength of will and inner choices. This relegates to the background collective ways of understanding the world, and ways we are shaped by culture, society and history.

Elements of colonization:

- Black = evil, white = good. This does not = universalized pre-Christian indigenous beliefs. As the article below explains, this is a Christian-style parable, perhaps originally spread by evangelical minister Billy Graham (in his version the teller is an Eskimo fisherman).

- Spiritual appropriation has high currency value. As an example shared in the comments section for this cross-posted article, if instead of “Native proverb”, something said “Settler author channeling Native sentiment”, it just doesn’t have the same impact. Or, if someone tried to spark interest in telling/spreading the story by saying, “Hey, I have this great Christian morality parable to tell!”

- Traditional Native stories don’t usually have a “moral” or direct “lesson” the way European ones do.

- The “old Cherokee” story becomes both missionary teachings and cognitive behavioral therapy dressed up in timeless wisdom to be disseminated.

Thanks, I would rather not bow to the white (man in a) wolf (costume) within.

This excellent piece dissects the wolf story, and connects this emblematic trend to broader forces of misattribution and appropriation. The author provides helpful critical thinking steps when engaging a wisdom story, and offers resources to connect with real stories:

Stories and sayings attributed to Native Americans have been floating around probably since settlers stopped spending all of their time and energy on not dying. I am not entirely certain why stories that never originated in any indigenous nation are passed around as “Native American Legends”, but listener beware.

“Hey so are you Cherokee?” “Na, I’m Irish, you?” “Well my great grandmother was a Cherokee princess…”

You’ve probably seen this one at least once:

An old Cherokee is teaching his grandson about life. “A fight is going on inside me,” he said to the boy.

“It is a terrible fight and it is between two wolves. One is evil – he is anger, envy, sorrow, regret, greed, arrogance, self-pity, guilt, resentment, inferiority, lies, false pride, superiority, and ego.” He continued, “The other is good – he is joy, peace, love, hope, serenity, humility, kindness, benevolence, empathy, generosity, truth, compassion, and faith. The same fight is going on inside you – and inside every other person, too.”

The grandson thought about it for a minute and then asked his grandfather, “Which wolf will win?”

The old Cherokee simply replied, “The one you feed.”

Wow, I’m just shivering with all that good Indian wisdom flowing through me now. Give me a moment.

Okay. I’m better now.

Well recently a tumblr blogger Pavor Nocturnus did the world an enormous favour and dug into the real origins of this ‘Cherokee wisdom’, providing some excellent sources.

This story seems to have begun in 1978 when a early form of it was written by the Evangelical Christian Minister Billy Graham in his book, “The Holy Spirit: Activating God’s Power in Your Life.”

“Hey cheer up, one day everyone is going to say they are related to us! And they’ll honour our culture with Christian-style parables!”

So wait…this is actually a Christian-style parable? Let’s just quickly read the story as told by Minister Billy Graham.

“AN ESKIMO FISHERMAN came to town every Saturday afternoon. He always brought his two dogs with him. One was white and the other was black. He had taught them to fight on command. Every Saturday afternoon in the town square the people would gather and these two dogs would fight and the fisherman would take bets. On one Saturday the black dog would win; another Saturday, the white dog would win – but the fisherman always won! His friends began to ask him how he did it. He said, “I starve one and feed the other. The one I feed always wins because he is stronger.”

Oh oh oh! I get it! Black is evil, and white is good! Traditional indigenous wisdom galore!

Um…wait a second. Do indigenous cultures also believe in black=evil, white=good? I mean, pre-Christianity? Anyone? No? I didn’t think so.

This kind of thing is harmful

These misattributed stories aren’t going to pick us up and throw us down a flight of stairs, but they do perpetuate ignorance about our cultures. Cultures. Plural.

Not only do they confuse non-natives about our beliefs and our actual oral traditions, they confuse some natives too. There are many disconnected native peoples who, for a variety of reasons, have not been raised in their cultures. It is not an easy task to reconnect, and a lot of people start by trying to find as much information as they can about the nation they come from.

It can be exciting and empowering at first to encounter a story like this, if it’s supposedly from your (generalised) nation. But I could analyse this story all day to point out how Christian and western influences run all the way through it, and how these principles contradict and overshadow indigenous ways of knowing. Let’s just sum it up more quickly though, and call it what it is: colonialism.

And please. It does not matter if this sort of thing is done to or by other cultures too. The “they did it first” argument doesn’t get my kids anywhere either.

The replacement of real indigenous stories with Christian-influenced, western moral tales is colonialism, no matter how you dress it up in feathers and moccasins. It silences the real voices of native peoples by presenting listeners and readers with something safe and familiar. And because of the wider access non-natives have to sources of media, these kinds of fake stories are literally drowning us out.

Start asking questions

If you are at all interested in real aboriginal cultures, there are some easy steps you can take to determine authenticity. I guarantee you that three short questions will help you weed out 99.9% of the stories plain made-up-and-attributed-to-a-native-culture. Ready?

- Which native culture is this story from? (Cherokee, Cree, Dene, Navajo?)

- Which community is this story from? (If you get an answer like the Hopis of New Brunswick you can stop here. The story is fake.)

- Who from that community told this story?

You see, our stories have provenance. That means you should be able to track down where the story was told, when, and who told it.

There are specific protocols involved in telling stories that lay this provenance out for those listening. There are often protocols involved in what kinds of stories can be told to whom, and when. Every indigenous nation is going to have their own rules about this, but all of them have ways of keeping track of which stories are theirs.

If you cannot determine where the story came from, then please do not pass it on as being from “x nation”.

Literary examples, problems with attribution

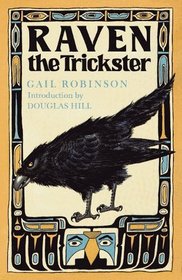

A friend picked this book up for me during a library sale. I immediately became uneasy when I read the inside covers. Here are some partial quotes that stood out for me:

“This book contains nine stories about the wily Raven…” No mention of where those stories originate other than from “the North West coast of the Pacific Ocean“.

“..the tales collected and retold here by Gail Robinson, a distinguished Canadian poet who has lived among the North American Indians and listened first-hand to the stories they tell…”

No actual communities are listed. No actual native people are named. There is zero attribution here. I have no idea if these stories are made up, mistranslated, or ripped off wholesale and profited from without any recognition given to those who carry traditional stories from generation to generation.

The stories are interesting, just like the “Cherokee” Two Wolves parable is…but I’m not presenting this to my children as authentic, nor should it be accepted as such without a heck of a lot more research into the origins of these tales.

Get the real stories!

An absolutely excellent resource for those seeking authenticity, is a blog called American Indians in Children’s Literature. There is a tonne of information there, which may be a bit overwhelming, but I urge you to start with the section on the right labelled “If You’re Starting a Library”. In this section are a selection of authentic books for different age levels and links for annotated reviews of each book.

There is also information on how to evaluate “American Indian websites“. A truly fantastic resource.

Another link available brings you to A Critical Bibliography on North American Indians, for K-12. Split into regions, you can find reviews of books which highlight any problems with the stories or the manner in which they were collected. There is also great information for educators and those wanting to understand how authenticity is important.

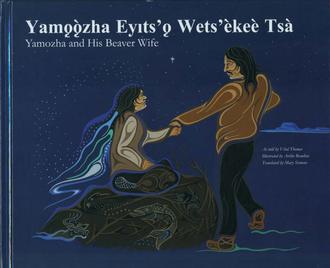

I also have a partial list of publishers who produce authentic indigenous literature. Some of it will even be available bilingually (English or French and in the original indigenous language). If I were to recommend something off the top of my head, I’d start with an absolutely fantastic series published by Theytus Books, published in English and Tłıchǫ Yatıì (Dogrib). All three of the books come with an audio CD as well.

I warn you, however. Authentic indigenous stories come from a different cultural context than you may be familiar with. That should be obvious, but I think that it bears noting. If you go into these stories expecting to have your cultural beliefs and norms reinforced, you’re doing it wrong. Trite western moral lessons are not going to be handed to you in our stories.

Listening to or reading authentic aboriginal stories means you are accessing different cultures. Please don’t forget that. And the next time someone tells you a “Native American” saying or story, ask yourself if it resonates with you because it’s really “indigenous wisdom”…or if it’s just a western story wrapped up in a cloak of indigeneity.

Thank you for such a clear discussion of appropriation. This topic wasn’t on the radar until recently and now it needs to be heard. I was trained as a Jungian analyst in Zurich about 15 years ago and it was shocking to me, even then, the way myths from many cultures served the Jungian theory, with little interest in really tracking down the roots of the story. As much as we carry on this practice in North America, Europeans don’t seem to have scratched the surface of this topic and are happily oblivious.

Wonderfully sensible commentary. I’m glad I stumbled upon your website.